Report from Computerville: Virtual Walkabouts and Master Narratives

REPORT FROM COMPUTERVILLE:

VIRTUAL WALKABOUTS AND MASTER NARRATIVES

Larry Owens, Dept. of History, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Dominique Thiebaut, Computer Science, Smith College

October 19, 2010

Published in Massachusetts Review, Spring 2011.

This is a tale about a serendipitous discovery that a book can become a place, indeed a place that might have special significance for the history of computing. But to make sense of that story, we must begin with another.

FORTY-ONE CENTS

Returning one day from class, Owens stopped at the food cart in the lobby of Herter Hall to buy yogurt for lunch. He gave the woman at the register two dollars. She gave him his yogurt and forty-one cents, saying “That’s my favorite change!” He had turned away, but did a double-take. “It’s one of each,” she said. A penny, a nickel, a dime, and a quarter. Forty-one cents. What was to Owens a pile of data – Why should forty-one cents have any more significance than thirty-nine, forty, or forty-two cents? – was to her a pattern rooted in the rhythms of her work day. If he made change as often as she, he too might have seen it. Patterns are about data as well as angles of observation.

PCS AND REVOLUTIONS

Mulling over this matter of patterns and piles, Owens recalled questions about the pc revolution that had roiled a recent seminar. Given its absence before 1975 and proliferation after 1981, that should be a straight-forward matter. But it turns out to be otherwise. Does “personal” refer to the appearance of objects small enough to own and lug home? Or to the development of systems that, through interactive responsiveness, give users the illusion of possession? Should the “C” in “pc” refer to an object or a process. Was it an instrument of revolution; if so, of what sort? Or was Bryan Pfaffenberger right that there wasn’t one?

Despite good scholarly work on a befuddled issue, there’s a veritable Gold Rush by aging pioneers and popular writers to lay claim to the revolutionary origins of the pc. Most play upon our cherished national mythology of Edisonian invention that reinforces long-standing beliefs in the character of American inventiveness. These heroic, entrepreneurial tales display patterns that have as much to do with present concerns as with the complex tangles of the past. Inspired by the Yogurt Incident in Herter Hall, might be possible to locate an angle of observation closer to the matters at hand? A vantage point that would also lay before us a panoramic view of the whole territory of computing? What personal machineries might then be seen!

Several summers earlier Owens had, in fact, stumbled on an exquisitely relevant pile. In a used book store in Henniker, New Hampshire, he found a copy of Anthony Ralston’s Encyclopedia of Computer Science. Innocent at the time of its significance, he later discovered that Ralston was an authoritative reference on computing – an enormously informative, learned, and even funny work that would go through at four editions. His was the first edition of 1976. No entries on the pc, the Internet, or even email! Wow! A pile of data, a vantage point, a panoramic overview by observers who didn’t yet know the end of the story. What patterns might be found in this pile of data? He decided to graph it.

COMPUTERVILLE

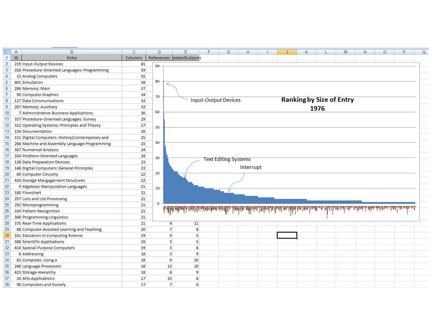

So he set to work. He reduced each entry to records in a database, recording the number of columns devoted to it, the number of references, and the number of related subjects. It took a while as he found himself reading many of the entries, important re-education for someone who had last learned computer science on the PDP-10 at Princeton in 1966. And as he labored, he began to fantasize. The entries became acquaintances and he found himself noting their wealth and status, connections and influence, trying to imagine the largely invisible associations they formed one with another. He imagined he was engaged in a prosopographical study of a town he came to call Computerville. If not Manchester in the 1700s, why not Ralston in 1976? Recalling Chicago before and after the Great Fire, he wondered if there might be a second edition. There was. It was available. And it had an entry on personal computing! Computerville in 1976 and 1983. What a wonderful way to bracket the birth of the pc. Madly, he set about reducing the second edition to lists and tables and graphs.

SOME ELEMENTAL DEMOGRAPHY

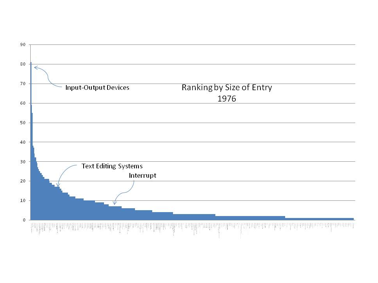

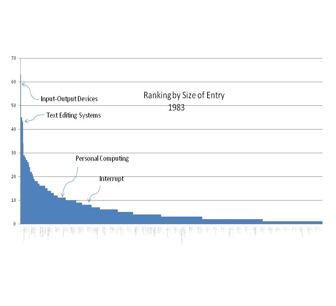

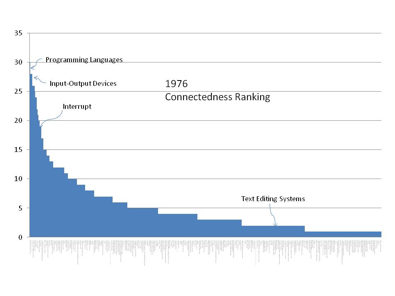

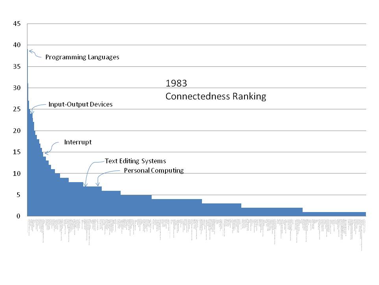

There are 481 citizens in 1976; 553 in 1983. Figures 1-3 show the top fifty or so ranked by the number of columns devoted to each. In both years, Input-Output Devices is at the top; in 1983, Computer Industry has nudged out Programming Languages for second. Personal Computer is of modest status, but Text Editing Systems has catapulted from minor status in 76 to fourth spot in 1983, maybe the most dramatic advance between the two editions. Then there is the Interrupt. Ranking entries not by columns, but by connections (Figures 4 and 5), reveals that the humble Interrupt, of only modest wealth, was an entry of great influence. We all know people like this who, while not belonging to the Athletic Club, get around, know everything about a place, and can get us in touch with the people we need to know to get things done. That’s an entry to remember.

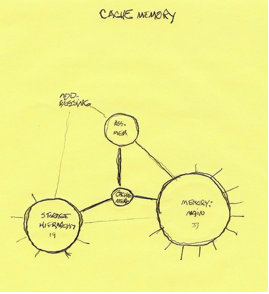

Connectedness, however, wasn’t easy to graph. First-order neighborhoods are clear; second-order neighborhoods and beyond are practically impossible to depict without help. Fortunately, Owens found expert assistance at Smith College: Dominique Thiebaut, a computer scientist engaged in a study of the visualization of data. Together, Thiebaut and Owens created a way to walk around Computerville.

VISUALIZING DATA

By good fortune, Thiebaut had been exploring methods for the visualization of large networks. He transferred Owens’ Access databases to a MySql database server, storing the 1976 and 1983 encyclopedia landscapes into their own separate database. He was able to leverage many of the features of the Prefuse visualization toolkit , a collection of Java programs written by Jeff Heer of Stanford as a neighborhood exploration tool which has been named VisNomad. Prefuse figures prominently as the library of choice in several visualization projects created for the exploration of Knowledge Management Systems , of which social networks such as Facebook, or Wikipedia, form a growing and significant component. Encyclopedias, too, are knowledge management systems, and we can expect to learn much from the similarities existing between visual explorations of individual relationships in social networks and our visual walkabouts in the two encyclopedias.

VisNomad presents two different views of Ralston’s Encyclopedia, one an alphabetical listing of the entries and the other a two-dimensional network showing selected entries or nodes and their connections to their surrounding “neighborhoods.” Clicking on any of the nodes, either those appearing in the alphabetical list or those in the network view, triggers the visualizer to query the database server for additional neighborhood information which is then dynamically added to the graphic representation. Entries that are highly connected, that refer to many related subjects, are displayed in larger fonts than those that aren’t. Similarly, entries that are located in more central locations in the network are colored in darker shades of blue than those on the periphery of the network. Since it utilizes Java and MySql, VisNomad will provide public access to the visualizer through the World Wide Web and make it possible to store other encyclopedic information in the database for future visual exploration.

WALKING AROUND COMPUTERVILLE

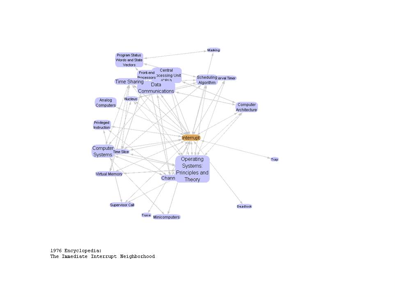

Intrigued by the Interrupt, Owens began his initial walkabout at that point.(Fig. 6) Early computers were brutish calculators, obsessed with the task in front of them, inattentive to anything else. Researchers at NACA’s Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory had purchased an expensive UNIVAC 1103 mainframe for batch processing but wanted it, when needed, to record real-time signals from a wind tunnel. In 1955, they developed maybe the first interrupt system to allow the UNIVAC to turn from one task to another, and then back, resuming where it had left off. The interrupt was incorporated into the 1103A and quickly spread as an essential element in computer design, allowing CPUs to interact with a burgeoning field of peripheral devices.

What neighborhoods were close by?(Fig. 7) Curious, Owens walked the short distance to Computer Architecture, where, appropriately, he found a picture of elements of a computer vying for attention: “Hey, Charlie!” “Here I am!” He returned to Interrupt and, this time, moseyed on to Minicomputers, where he learned that the growing ability to pack more elements onto chips was helping to overcome serious constraints: namely, elementary Input-Output arrangements and limited interrupt schemes. “[T]he sophistication of the interrupt system,” he read, “may be more important than machine speed or instruction repertoire.” From there Owens wandered to Microcomputer, a modest neighborhood indeed, with nary a sign of the personal computer. Continuing on to Intelligent Terminal, he discovered a prosperous area and learned about the importance of smart nodes in distributed networks and the increasingly blurred boundaries between machines large and small. He headed towards Terminals, with a stopover at Input-Output Devices, the largest of Computerville neighborhoods. A central hub, I/O details the vast assortment of devices to which mainframes and minis, largely, were connected. At Terminals, he learned the difference between batch processing and the fast interactive terminals showing up in banking machines, airline reservation systems, supermarket checkouts, assembly lines, and data processing. That day’s walkabout ended at Text Editing Systems, still a small place in 1976, where faint signs were detected of what would come to known as the pc in mentions of Ted Nelson’s Hypertext and Doug Engelbart’s work on GUI’s and word processors at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center.

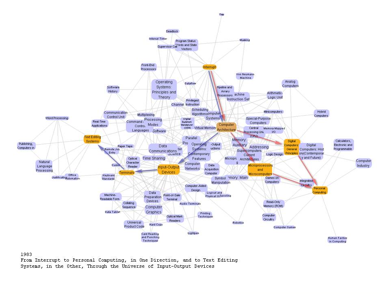

Then, like Dr. Who, Owens traveled to 1983, sometime after IBM’s introduction of its standard-setting Personal Computer.(Fig.8) The Interrupt neighborhood showed little change although the entry had been thoroughly revised, now dividing into large machines and a section on microprocessors that featured Intel’s 8080 and the creation of the first undisputed pc, the 1975 MITS Altair. He was reminded that since “most operating systems are interrupt-driven, computer designers had to deal with a “great diversity of interrupts” amidst “a rich variety of external devices.” He wandered back to I/O Devices and a vastly expanded neighborhood of needy peripherals, hearing as he passed through the neighborhood of Computer Architecture that designers had “begun to refine and ‘civilize’ the interrupt systems of computers.” At Terminals, he learned that, because of increasingly abundant microprocessors, it was now “possible to package an entire general purpose minicomputer inside an interactive terminal.” A stroll to the expanded environs of Text Editing Systems found him in a neighborhood of now familiar landmarks like word processing, office automation, natural language processing, and publishing.

Another tour led from Computer Architecture to Microprocessors and Microcomputers. The micro business was obviously booming, with fifty different microprocessor families going into industrial control devices, minis, and personal computers. A bit further and Owens found himself in the new neighborhood of the PC.(Fig. ) The area had an uncertain character, with both inexpensive micros owned by individuals for non-business purposes and the single users of networked interactive terminals designated as personal computing. “[T]echnically,” he read, “many of the video games currently on the market must be classified as personal computers.” For the future, “the percentage of recognizable, general-purpose digital computers in the hands of the general public…will likely remain quite small in comparison to the number of televisions or telephones in similar use.” The expectation seemed to be that the significant development of the personal computer would be as a smart terminal in area networks, allowing the public to tap into centralized databases.

A REPORT FROM COMPUTERVILLE, PART ONE

In wandering around Computerville, we have seen things that mattered and appreciated odd perspectives. There were only modest signs of the PC. Maybe that’s because, given the lag in publishing, Ralston 1983 is still just too early; maybe it’s there but in a suburb over the hill, dismissed or overlooked. But it’s also possible that, at least in part, our popular notion is a mythopoetic conceit, a bit like Edison’s lamp and its simple inventor, 99% inspiration and 1% inspiration and a whole lot easier to embrace and understand than the messy, complex, diffuse, and socio¬technical systems in which it was but a modest actor. What impressed the city fathers at the time was the fact that computing machines were getting smaller, cheaper, and more portable: thus able to serve as windows to an exuberantly expanding peripheral universe, particularly as smart nodes in expanding networks. We searched for the PC; we found the intelligent terminal pointing towards new sorts of virtual communities.

Eccentric as these Computerville wanderings might be, they have revealed potentially rewarding “dig sites.” First, there’s gaming. Somehow, we’re not surprised that Homo Ludens should embrace this protean, playful machine as a defining element of culture, even in these early days. Then there’s that dramatic explosion of interest in text-editing systems. As Ralston 1983 puts it, “In 16 years, a giant industry has been created.” For those of us who use these machines to create words and worlds, it doesn’t seem a reach to find revolution here to rival Gutenberg’s. Do we have good studies of text-editing software? Also, the office environment might have been transformed by intelligent terminals like Xerox’s Altos, but haven’t we as individuals, by imbedding software like Microsoft Office in our PCs, also been reshaped into particular sorts of users?

And let’s not forget the Interrupt. As we all surely remember, Tracy Kidder once suggested in The Soul of a New Machine that, if one had the eyes to see, one could find organizational culture in microelectronics. Could one not use the humble interrupt – with its graceful design and civilized disciplining – to explore the complex sociotechnical negotiations that surely occurred in the design of network architectures?

REPORT FROM COMPUTERVILLE, PART TWO.

There is a master narrative in the history of computing that goes something like this : there emerged during the Scientific Revolution the first mechanical devices intended to perform mathematical calculations and thereby represent the mechanical workings of the human mind. The great analytical engines of Charles Babbage continued this evolution, which came to a climax towards the end of the Second World War both in Europe and in the United States. Machines like ENIAC, Whirlwind, and UNIVAC – and their inventors - are the iconic embodiments of this evolution. Computing machines continued to become more powerful by becoming larger until the microelectronics revolution driven by the ICBM made smaller devices possible and made possible the emergence of the minicomputer. The sudden appearance of the personal computer within this narrative represents somewhat of a complication, for it’s a machine that lacks in its beginnings both purpose and market beyond the assorted imaginings of hobbyists and cultural revolutionaries. Nevertheless, its story echoes the central themes of our Edisonian tradition by emphasizing both the machine itself and its heroic inventor. There is, however, an alternative narrative that became clear in our wanderings through Computerville. This storyline hinges not on the machine as an indepent creation but as a component in increasingly complex networks. As has been noted, we searched for the personal computer, but found the intelligent terminal pointing towards new sorts of virtual communities.

This alterntive narrative takes its cue from James Beniger’s control revolution and Thomas Hughes’ study of electrical power, works which stress the growth over the last few centuries of complex technological systems that produce continuing crises in control and management, and from Wolfgang Schivelbusch’s notion of the machine ensemble. Schivelbusch’s approach is intriguing because, while it doesn’t diminish the place of the single machine or its status as a representation of industrial culture with its associated ideas of invention and discovery, it does stress the manner in which more modern machines often develop as components of larger technological systems. Most of these systems – from railroads, telegraphy and telephony, to large-scale universal power systems - have evolved in order to enable the movement of both goods and information across increasingly larger networks and territories. We should remember that recent history of computing is, by and large, solidly ensconced with the growth of networks like SAGE, the ARPANET, Internet, and Web; and with WANs, LANs, and the office networks we depend on and take for granted – within, that is, networks, at the same time, both social and technical. This is the narrative within which the modern computer needs to be embedded – and at which our Computerville wanderings hint. It’s a story not so much machine-centric as systems-centric, in which personal computers serve as links with and gateways to pervasive networks of all sorts and sizes – still an Edisonian story, maybe, but one which dramatizes not the eccentric, individual genius of American mythology and his amazing inventions but the network-minded system-builder who inspired Sam Insull.

REPORT FROM COMPUTERVILLE, PART THREE.

The knowledge gleaned from our particular tours, frankly, might not bear up against the experiences of other wanderers. Other lessons are surely less eccentric. Outdated reference works, even those in fields with especially short shelf-lives, need not be relegated to the dusty shelves of forgetfulness. They are very much worth our attention. Then there is the matter of the mutual relationships between books, readers, and editors. We need to remember, on the one hand, that Computerville was a company town. The neighborhoods visited here reflect the state of the computing art, the state of mind of the editors and authors who put in the hard, probably contentious, work of selecting topics and writing entries, and the separate wanderings of a curious historian and an intrigued computer scientist. But we also know, on the other hand, that books and readers mutually construct one another; readers poach for their own reasons in preserves managed by authors and editors.

There is much about these works and the virtual places to which they give access at which we can only guess, beyond whatever arguments might have preoccupied the editors. How were they used, if they were used and not just bought, by those with an interest in this new technology, whether amateurs or the practitioners of a new discipline in the process of formation, searching for professional identity and the neighborhoods that might define the geography of a field? That’s a difficult question to explore. Both Owens and Thiebaut have, however, acquired new respect for old books. Even outdated reference works like Ralston ‘76 and its successors might very possibly help reveal the complex literary processes that contribute to the forging of new disciplines, processes to be found not just in editorial machinations, but in the manifold explorations of their many ordinary readers.

This tentative survey of Computerville is reminiscent of a passage in Michel de Certeau when he found himself at the summit of the World Trade Center looking out over the “wave of verticalities” that defines Manhattan. Here he found synopsis, the totalizing vision of city planners; a vision, he noted, always at risk, for the “ordinary practitioners of the city live ‘down below,’ below the thresholds at which visibility begins. They walk….” It is in the tangled narratives of those walkabouts that he seeks the continual making and remaking that resists and subverts synopsis. Computerville is a bit like that, a geography of the mind, a virtual Manhattan exiting in tension between the vision of its editors and the narratives of its readers, all of them working to find their places in a new technological landscape.