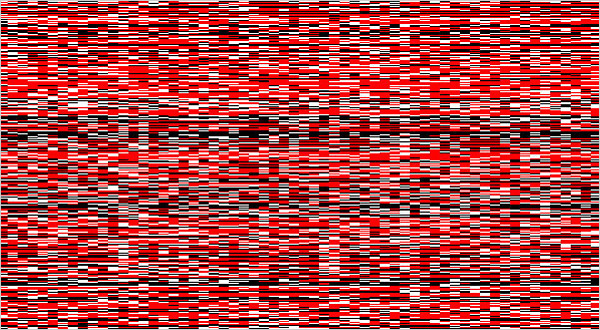

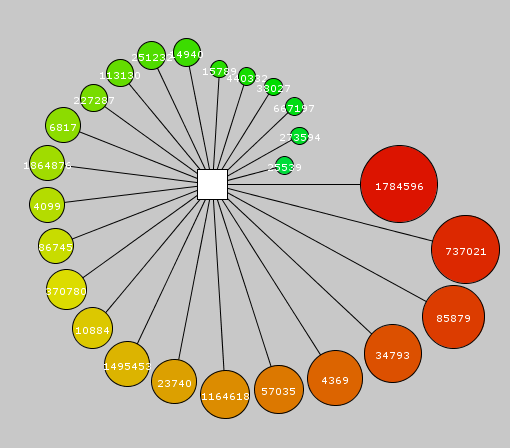

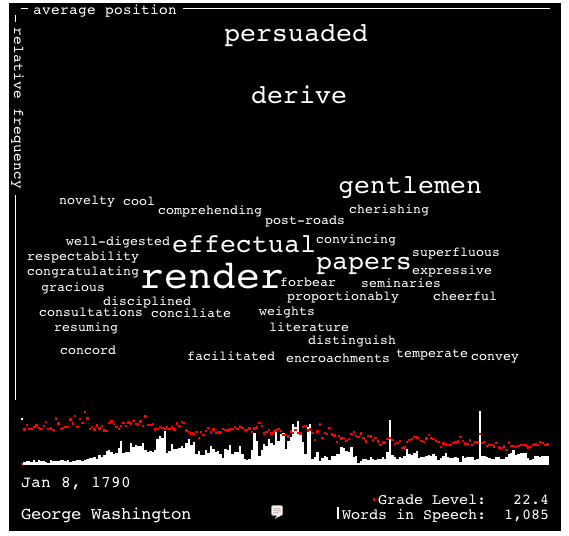

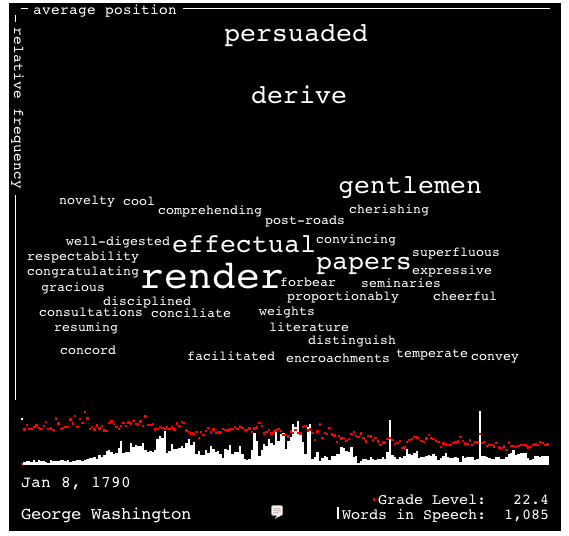

http://stateoftheunion.onetwothree.net/

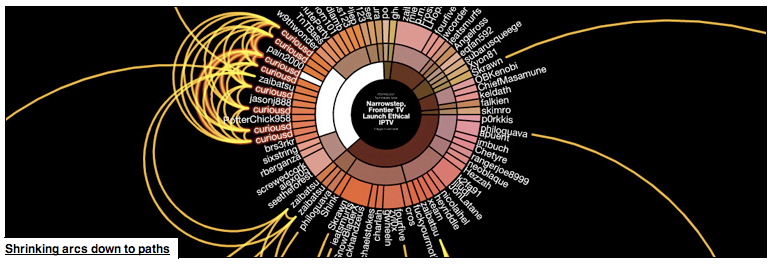

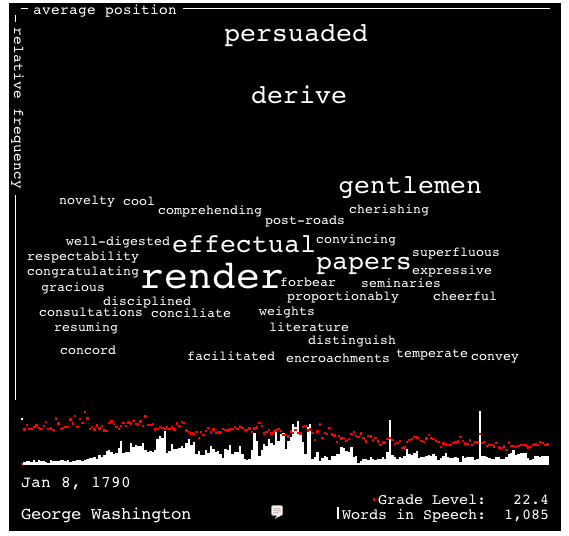

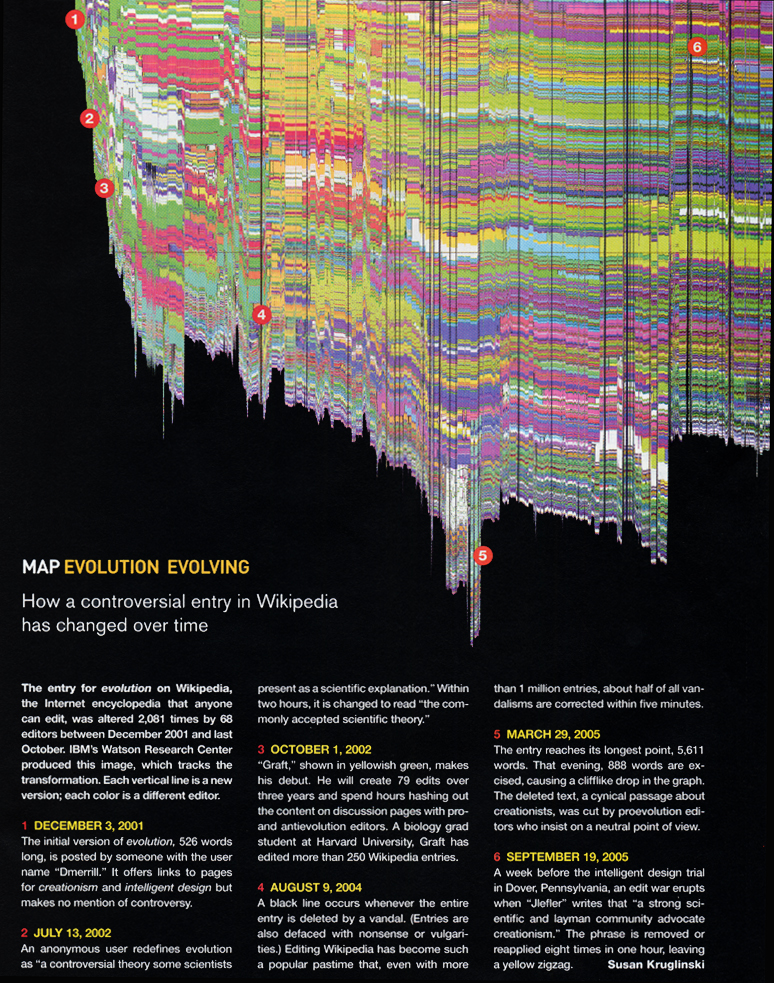

This is done with processing, and truly interactive. As the arrow key is moved left or right, we move by one year backward or foreward, respectively, and see in red the words used the year before, and in white the words of the current year. Cool…

The link contains an interesting essay, reproduced below:

The {Sorry} State We Are In

by Brad Borevitz

The triumph of iconicity over rhetoricity–call it the society of the spectacle, call it what you will. The change has certainly not gone unobserved. And yet, we are likely to blinker our awareness of the situation–and imagine that the mechanisms of our governance continue unaffected–that the institutions of democracy are somehow untouched by these changes. But how can this possibly be the case?

A democratic system of government depends on communicative practices that are founded on rhetoric: an art of persuasion. This implies a public sphere as the ground of a competitive exchange of argument and counter argument. Reason theoretically rules such a domain, where syllogistic conventions determine the outcome of a competition of ideas based on the strength of evidence and the logical coherence of their exposition.

What has displaced this rhetorical arena is a screen on which assertions are projected. It may be that these assertions compete for attention, but they don’t entertain argument or tolerate critique. Assertions are immune from denigration based on counterfactual evidence, or the revelation of faulty logic. Competition in this environment is a matter of precedence, authority, style, volume, frequency, and ultimately saturation.

Contemporary political ideas, which take the form of memes circulating in the soup of our media saturated world, are formally equivalent to the fragments of iconic identity circulating as agents of corporate entities, the brands. Politics is branding, the media practice of producing identity as awareness and desire, through the deployment of declarative language and image.

Not only have commercial interests produced a scarcity of actual public space by their domination of the landscape and their occupation of the commons, they have gained almost total control over the virtual spaces of communication, and colonized the language of political discourse itself.

In this atmosphere, the public debate over ideas is obsolete, if not impossible. The significance of such a change is immense. In Benjaminian terms, politics enters the realm of the aesthetic, a situation symptomatic of fascism.

How is it that we have arrived at this state? Why are we so surprised as we wake now to the nightmare? After all, here in the U.S., the president has been informing us of the state of the union from the year the constitution was ratified. Were we not listening to the message–not reading in this text the signs of transformation? When was it that the words addressed to us changed from having a rhetorical significance to an iconic one? When was it that the words last demanded our understanding, and when did they come to simply demand that we buy in?

A Form

The State of the Union address is a particularly apt data set to explore for clues about the change in political language: it is a remarkably consistent form available annually over the entire history of the United States. Article II Section 3 of the Constitution inaugurates the practice:

[The President] shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient …

Very quickly, the address acquired a conventional form as a yearly message delivered by the office of the president, at the beginning of the year, to the congress, the representatives of the people. This consistent structure, which endures over the course of U.S. history, is what allows for a useful comparison between actual instances of the address. Such comparisons would be difficult to make otherwise between more random fragments of political discourse not regulated by a uniform temporal frame and an archetypal structure of address.

In the ceremonious address in congress, when the president is announced, he is called, “the president of the United States,” and not mentioned by name. The State of the Union is specifically not delivered by the person of the president–the specific officeholder of that position–but rather, the office of the president–that space of authority that the person merely occupies temporarily. Even if he signs his name to the document (if it is written), the text has very rarely been composed exclusively by him–it is merely approved or intoned by him. Presidents have always had help with writing, starting with Washington who relied on Hamilton for this service; though, Coolidge (1923-29) was the first to have an official speechwriter on staff.

In addition to the hypothesized change in language between the rhetorical and the iconic, the State of the Union has, from the beginning, been subject to various tensions and trends both political and linguistic, which also affect its language. One of these is the opposition between written and oral delivery of the message. The address was first given in person, but starting with Jefferson in 1801, the message was written and delivered to congress where it was read by a clerk.

Jefferson’s objection to the spoken format was the inappropriately monarchical implication of the address, given its similarity to the imperial practice of the speech from the throne. From Jefferson, until Wilson in 1913, the message was written, and referred to as the “President’s Annual Message to Congress.” The contemporary usage of the term “State of the Union Address” starts with Roosevelt in 1935. With the exception of the years 1919-20 (Wilson), 1924-28 (Coolidge), 1929-32 (Hoover), 1944-45 (Roosevelt), 1946 and 1953 (Truman), 1956 (Eisenhower), 1961 (Kennedy), 1973 (Nixon), and 1981 (Carter), all messages since 1913 were delivered orally (in 1945 and 1956 they were broadcast as radio addresses, though they delivered to Congress as written messages).

The oral delivery of the address in the modern period coincides with a tendency towards broader dissemination of the message in the press and the media more generally as the century progresses. 1923 brings the first radio broadcast. In 1947, the speech was televised. In 1965 it was moved to the evening hours, presumably to be made accessible to the working person. And, in 2002, it was available live via the web. The audience for the message had always included office-holders in government, the direct address of the public via broadcasting, would certainly impact the language used. Broadcast demands a different, probably less formal, communication style, and an extra self-consciousness in targeting the more populous and diverse audience. Simultaneously, speech in general has likely become less formal.

Given that affirmation or rejection rather than argument are the possible responses to anti-rhetorical speech acts, the applause of the live audience, the congress, the supreme court, and dignitaries assembled in the capital building, takes on a special importance and contributes significantly to the length of the address. Applause are, more and more, a partisan affair, with the members of the president’s party responsible for most of the acclamation, and the members of the court abstaining from all but the most perfunctory and polite participation. In this respect, the speech comes to resemble a sporting event with a partisan audience both present and remote, and with referees maintaining their impartiality at the sides. Since Bush’s first speech in 2002, White House transcripts have contained parenthetical notations of the applause and laughter.†

The content of the State of the Union messages certainly vary according to the issues of the day, but they also contain constants: the words that constitute the mythos of our governance and the machinery of its ideology. With characteristic eloquence, Jimmy Carter writes in the 1979 address:

As long as I’m President, at home and around the world America’s examples and America’s influence will be marshaled to advance the cause of human rights.

To establish those values, two centuries ago a bold generation of Americans risked their property, their position, and life itself. We are their heirs, and they are sending us a message across the centuries. The words they made so vivid are now growing faintly indistinct, because they are not heard often enough. They are words like “justice,” “equality,” “unity,” “truth,” “sacrifice,” “liberty,” “faith,” and “love.”

These words remind us that the duty of our generation of Americans is to renew our Nation’s faith, not focused just against foreign threats but against the threats of selfishness, cynicism, and apathy.

Despite Carter’s protest to the contrary, those key words he claims are not heard, are, in fact, heard constantly: the word “justice” appears in 180 addresses a total of 752 times. It is a staple of presidential expression. To be fair, other of these words have been less popular of late in State of the Union speeches, and may also be less popular in colloquial speech. Certainly justice, liberty and faith, at least, are constantly in our ears.

| Word

|

Speeches

|

Occurrences

|

| Justice

|

180

|

752

|

| Equality

|

85

|

149

|

| Unity

|

60

|

102

|

| Truth

|

69

|

101

|

| Sacrifice

|

57

|

90

|

| Liberty

|

137

|

306

|

| Faith

|

134

|

341

|

| Love

|

54

|

78

|

| Freedom

|

154

|

676

|

| Peace

|

207

|

1821

|

| War

|

206

|

2631*

|

*Not including plural forms

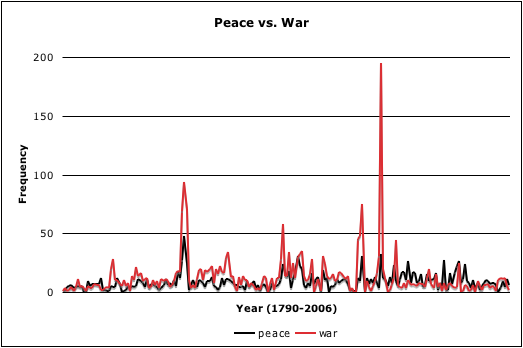

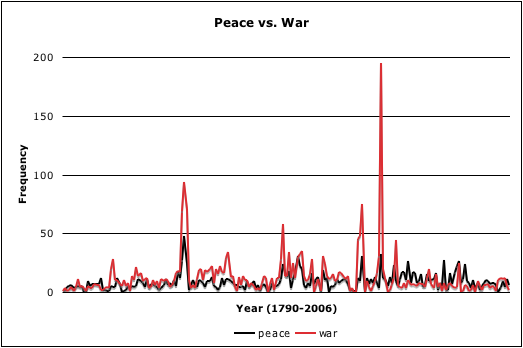

A word like “Freedom,” a Bush favorite, is in 154 of the speeches. The words “peace” and “war” occur together in 200 out of the 214 addresses–fully 93% of them. If there is a single issue, which dominates the corpus, it must be this. Practically the first thing out of Washington’s mouth in the very first speech was: “To be prepared for war is one of the most effectual means of preserving peace.” In that sentence, it is as if he sets the agenda for the next 200 years of history and inaugurates the confusion, which persists to this day, over the meaning of these two simple words.

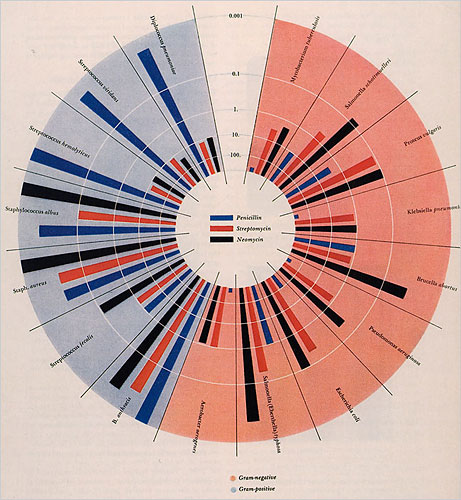

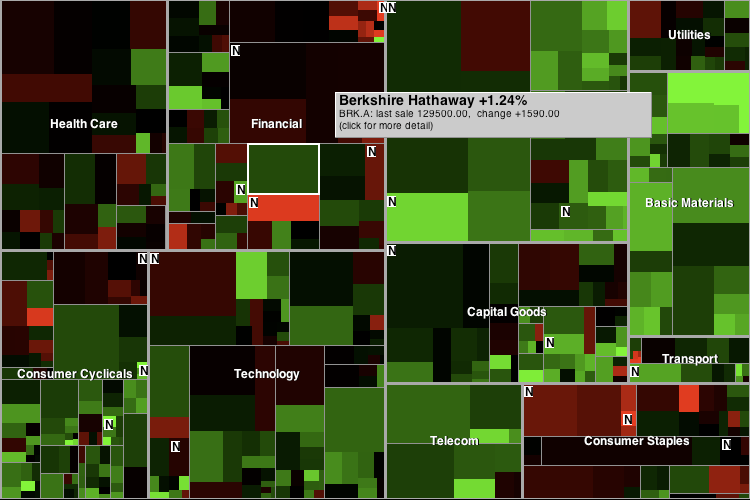

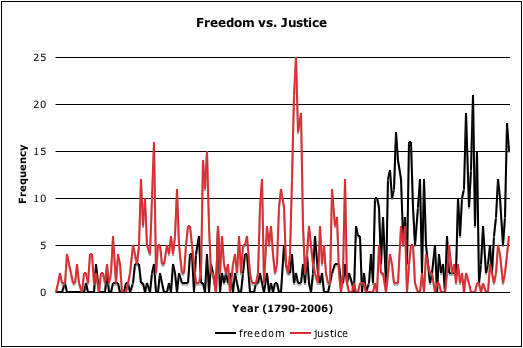

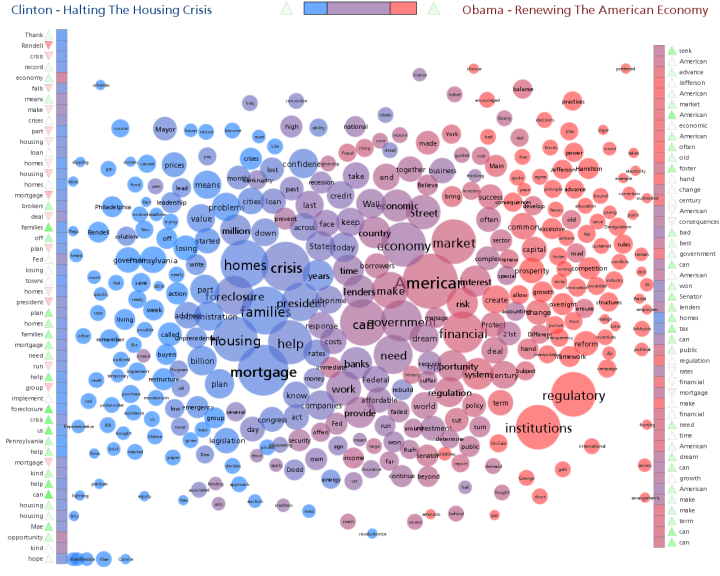

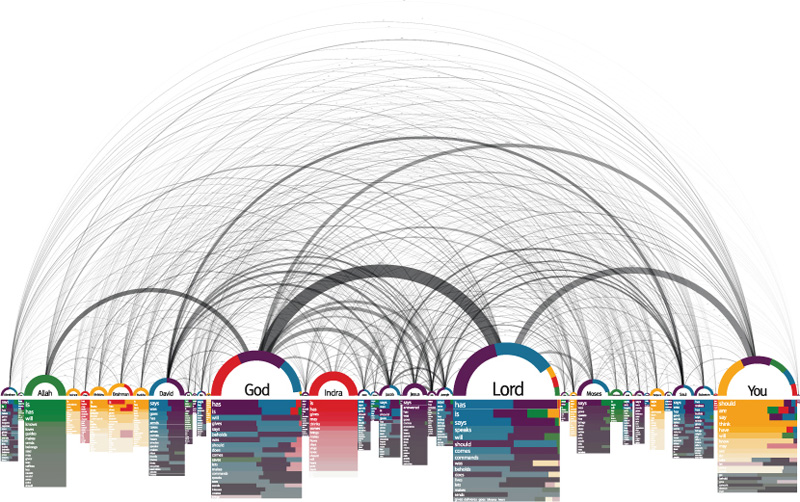

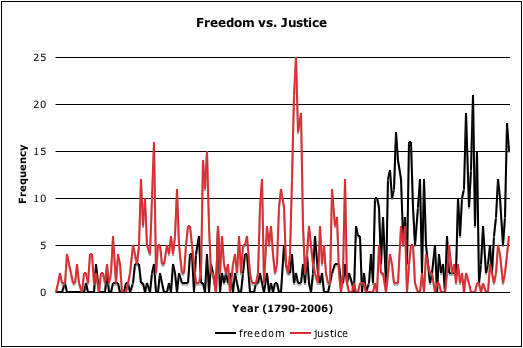

Each iconic word has a history of usage, a profile of its popularity, and a trace of the contest between words within the ecology of political language. Visualizing this history gives us insight into these struggles. The words “peace” and “war” seem bound tightly together in their rhythmic march into the future, but “war” peaks dramatically during major conflicts leaving peace far below in its shadow. Between “freedom” and “justice” the dynamics are livelier. Whereas “justice” seemed the favored value trending upwards from the beginning, World War II marks a dramatic reversal of fate. “Freedom,” it seems, is now more important than “justice.” And that just might explain some things.

Another Reading

The counting up of words suggests a different sort of reading practice. There is reason to be skeptical of the positivist implications of a statistical analysis of language, but there is also motive to appreciate and explore the current vogue of quantitative methods. There is something compelling in the urge to empirically examine this particular corpus for clues as to how things have gone horribly wrong. Maybe we can no longer bear to listen to the address, or maybe it has become impossible for us to read it. There are certainly few who would be willing to scrutinize all 3000 pages of our legacy of 214 messages from the president. Perhaps counting is a defense against the spell of iconic language. It may be that counting is simply the automation of a practice that we participate in already, as we measure unconsciously our saturation in the messages of the media–as they work us over completely.

Is it a problem to conceive of reading practices that satisfy the will to process the material, to refine it, to empty it of its gold, but not necessarily to understand it? We fear succumbing to the desire to consume the messages, for consumption entails risks and investments that we will not bear. It is too much. The scanning of words abstracted from their context produces a reading that is dependent on iconic recognitions and specifically not on rhetoric. This is an analysis that is blind to motive but cunning to structure–or is this an analysis at all? If it is true that rhetoric is lost, it is a way of reading that those dead texts deserve.

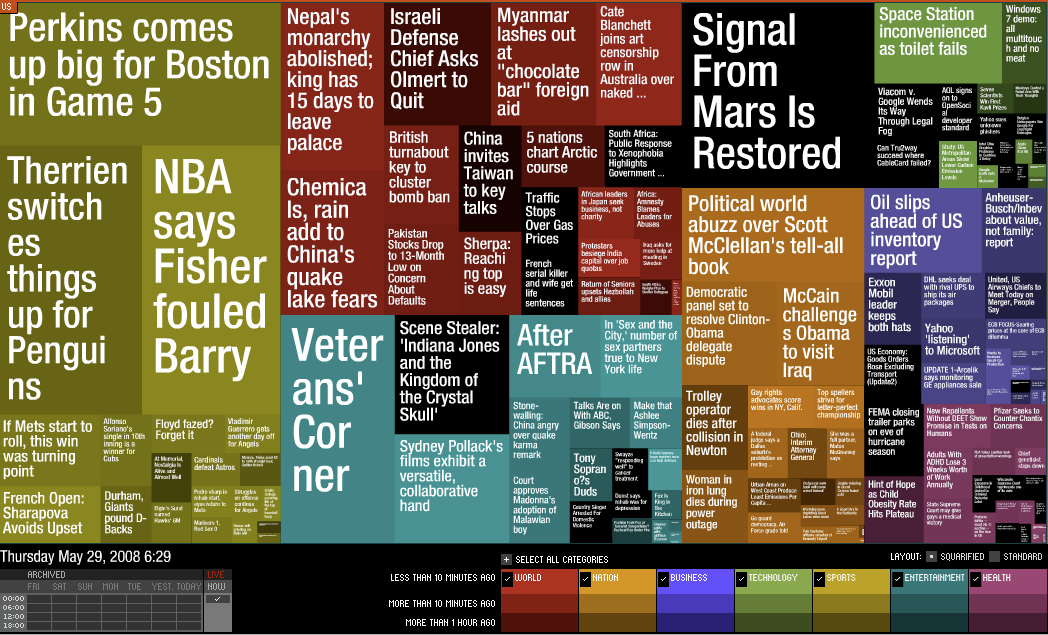

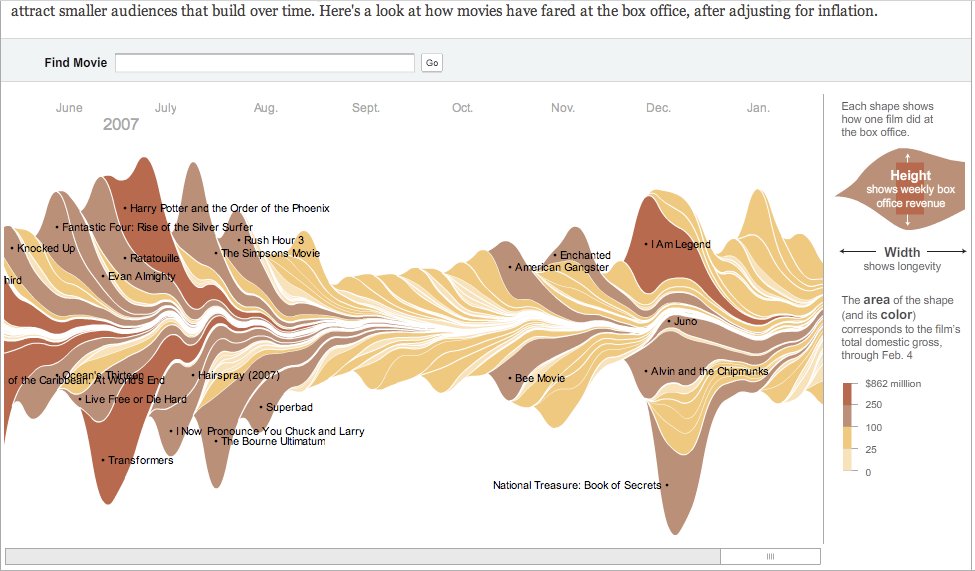

Certainly, such practices already exist, separating attention into surface and depth: the scan and the mine. The task is divided between our parts: our silicon organs, and our fleshy ones. Applications of this kind surround us: search engines, maps of markets (Marketmap), of headlines (Newsmap), of books (Amazon’s concordance). We are increasingly aware of the degree to which our lives are the texts that are mined and scanned by industry and government alike. A quantitative reduction is not simply a violence, a prelude to injustice, a methodological inadequacy, a mistake, or a failure, it is a practice matched with a circumstance.

The master’s tools are turned against him. We can envision a Total Information Awareness program of our own and aim its tentacles at government documents. It is an ironic pleasure to scan in seconds the one-and-a-half-million-word corpus of the State of the Union for important keywords and significant characteristics, even as the government’s programs mine our personal data for incriminating evidence–how much more so with the revelations in late 2005 that domestic spying was not simply post-9/11 paranoia, that the theoretical capabilities of the now defunct Information Awareness Office had actually been deployed out of the dark side of the Defense Department.

† The version of the Bush addresses that are published in the Congressional Record contain only a few scattered notations of applause, mostly at the begining and end of the speech, while the White House transcripts (as well as those on CSPAN) include upwards of 50 parenthetical notations of applause in each.